With the introduction of the Income Tax Act 1914, the positions of accountant and deputy accountant were also introduced at the Tax Administration. In 1916, many new deputy accountants were hired, including two women: Miss E. Fennema, who began in Rotterdam on 21 September 1916, and Miss M.F. van ‘t Hoff Stolk, who began in Amsterdam on 12 October 1916. In 1918, two more women deputy accountants arrived: Miss E.C. van Slogteren in Utrecht and Miss M.A.C. Schutter in Groningen. Miss J. Duitz followed in Amsterdam on 7 February 1919, the last appointment of a woman for the time being. Meanwhile, men from the first cohort had already been promoted to accountant.

At the end of 1919, a female candidate was rejected. We know this because it came up during parliamentary questions. The minister responded that there were doubts within the department: he stated that the trial period involving a few women had shown that women were not suited to the profession. The women who were employed at the time were not going to take that lying down! In April 1920, they jointly requested the minister to inform them of what the problem was, since they had only received good appraisals from their supervisors. Since there were no problems with their performance, the minister should restore their reputation.

The ministry took two months to formulate a response: since there were no negative reports, no one’s reputation needed to be restored. The minister did not feel there was any reason he should be taken to task over the matter and did not retract his words. The recruitment of exclusively male candidates continued. Newspapers covered the issue. The National Bureau for Women’s Labour identified the inconsistency and paid attention to it in the August 1920 issue of their monthly bulletin.

All to no avail.

Fennema

Miss Fennema (hired in 1916) passed her accountant’s exam on 11 December 1922 and was promoted to accountant in Amsterdam with effect from 1 February 1923. She subsequently opted to go into private practice. On 1 May, she retired at her own request, and on 17 May the Bureau for Taxation and Accountancy, headed by E. Fennema, opened in Heemstede. Her husband W. Duchâteau – also from the Tax Administration – and other men joined the firm. But she remained senior partner of the successful firm that now had multiple offices.

Mrs Duchâteau-Fennema was committed to women’s issues. She served on a committee investigating the question of how working women were taxed. In 1953, the committee advised the House of Representatives to grant married women their own tax-free allowance and abolish the comparatively higher separate tax rate for married women. The recommendation was not adopted. The law remained unchanged until 1973 when married women started to be taxed on their own income, but their tax-free allowance was still only 20% of their husband’s.

van ’t Hoff Stolk

Miss van ‘t Hoff Stolk (from the first cohort of 1916) never married and remained with the Tax Administration her entire working life. She either lacked the ambition or the ability to pass the account’s exam, as she remained a deputy accountant until her retirement in 1954, the year she turned 66.

In 1935, she became president of The Hague branch of the Business and Professional Women’s Club, a society that represented the interests of working women.

Duitz

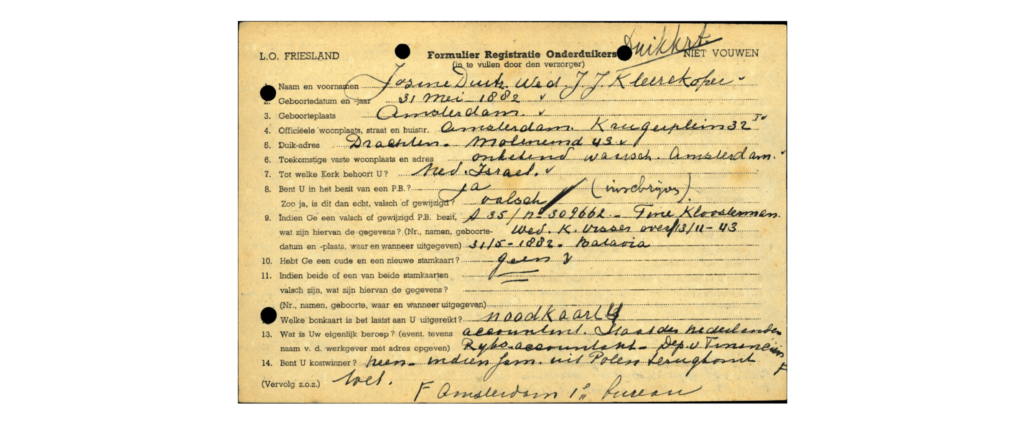

On 22 March 1922, Josina Duitz (born 1882, hired 1919) married synagogue council secretary and religious education teacher Jacob Jesaya Kleerekoper, who was a year her elder. From then on, she is listed in the yearbooks as Mrs J. Kleerekooper née Duitz. The 1924 law was apparently no obstacle to her continuing to work as a married woman (she was then 42 years old). In fact, she passed the accountant’s exam after her marriage and attained the rank of accountant on 19 January 1926. Although Jacob had died just before this, on 8 January 1926, Josina remained listed in the yearbooks as Mrs J. Kleerekoper-Duitz until World War II. As of 1941, Josina disappears from the yearbooks. She had fallen victim to another law: all Jewish civil servants were dismissed by order of the German occupation authorities.

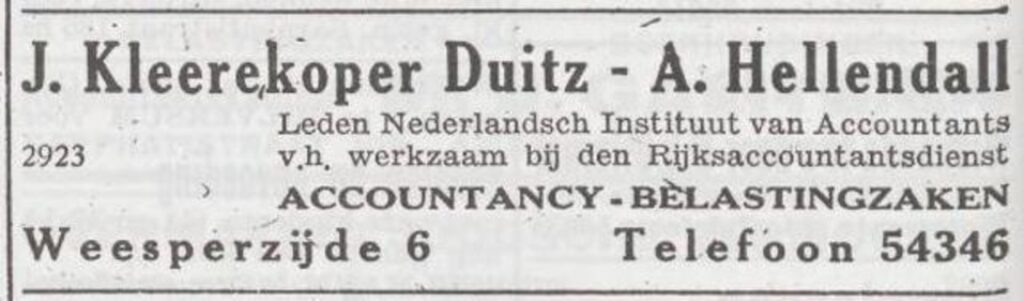

She responded to this injustice by opening her own office at Weesperzijde 6 in Amsterdam – where she also lived – with a colleague who had been similarly dismissed, Deputy Accountant A. Hellendall. This venture was destined to fail: all Jewish life in Amsterdam would be destroyed.

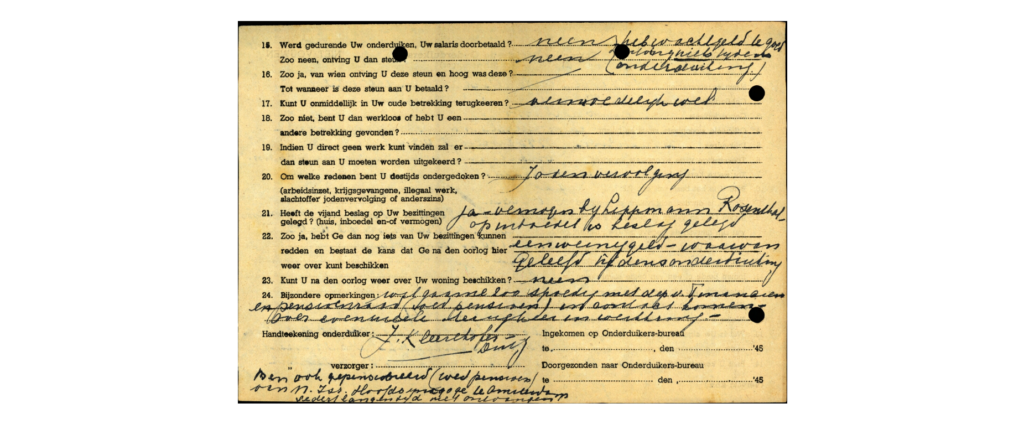

Mrs Kleerekoper went into hiding in Drachten with a fake identity card and survived World War II under the alias Tine Kloosterman. On her onderduikerskaart (registration card for people in hiding), her answer to the question of whether she would get her old job back was: ‘most probably’. And she said she would be the breadwinner when her family returned from Poland. And indeed, on 16 July 1945, she regained her old position as accountant at the 1st Bureau of the National Audit Office in Amsterdam. However, her relatives had died in Auschwitz and Sobibor.

She appears in the post-war yearbooks as Widow J. Kleerekoper-Duitz, even though by then she had been widowed for almost 20 years. In 1948, at age 60, she was no longer in government service. Josina died on 20 December 1952.