The Exhibition Texts in English

INTRO

Enter the world of OPIUM and discover how the Netherlands built an opium empire, with far-reaching consequences. Go back in time to the heroin epidemic at the end of last century and all the way to the 17th century when the Dutch East India Company began trading in raw opium.

The Netherlands traded opium for many years and even had its own state opium factory in Batavia. From purchasing to production and from sale to distribution – the entire opium chain was once completely owned by the Dutch state. Until 1919, opium was a legal product in the Netherlands.

Of all the remedies it has pleased almighty God to give man to relieve his suffering, none is so universal and so efficacious as opium

Sydenham

GRAFFITI

Opium sale fills treasury

56,000 kilos of raw opium imported per year by the VOC (1619 -1799)

Largest heroin seizure: 2,400 kilos

QUOTES USERS

Heroin addict 1977:

To get money for my next fix, I have broken into hundreds of cars. Every time when I got out of prison, so many had died. Using heroin, it’s like taking an advance on death.

Opium addict Java 1885:

When my rice harvest failed, I sold three buffalos from my father’s inheritance in order to buy opium.

Oxycodone addict 2019:

During my treatment I was happy with the medication, it felt like a warm blanket, which I needed against the severe pain.

Opium addict Java 1887

For a year I didn’t use at all. During the first three months, I felt sick every day.

Opium addict Java 1885:

Why shouldn’t I use? Someone who uses, feels strong, light and without wishes.

TIME PERIODS

TIME PERIOD 1: 1920-2024

I OPIOID PROBLEM

Opioids such as oxycodone and fentanyl are narcotic drugs with a high risk of addiction. Their use in the Netherlands has increased sharply, especially that of oxycodone. In 2017, four times more prescriptions were written than in 2010. Apart from being available on prescription, these drugs are also used recreationally and offered for sale on illegal websites.

The situation in the Netherlands is not the same as in the US, where there are millions of oxycodone addicts, users of ‘zombie drugs’ and some 100,000 overdose deaths every year. But we do have a problem.

In 2022, recommendations were made on prescribing opioids for as short a time as possible and writing repeat prescriptions only after a new consultation. Official figures show a decline, but that does not mean abuse of these addictive painkillers has stopped. Little is known about illegal use.

II HEROIN EPIDEMIC

Around 1970, Chinese triads (internationally operating organised crime syndicates) introduced a cheap form heroin into the Netherlands. Known as ‘brown sugar’, it was sourced from opium farmers in Thailand and Burma. The Netherlands soon had over 10,000 addicts, most of them in Amsterdam – the Vondelpark was full of them. In the early 1980s, Turkish criminals largely took over the lucrative trade when Turkey became a transit country for a new heroin pipeline through countries like Afghanistan and Pakistan.

In 1987, Perron Nul (Platform Zero), a shelter, was set up next to Rotterdam’s Central Station. Addicts could get methadone and clean syringes there. In 1994, the municipality closed Perron Nul because of the trouble caused by the large influx of addicts from all over the Netherlands.

The number of new users had decreased sharply by the end of last century. The many overdoses and diseases like HIV had given heroin a bad name. Most of today’s older addicts, the survivors, are under supervised treatment.

III THE CHINESE IN THE NETHERLANDS

When a major sailors’ strike was looming in 1911, Dutch shipping companies hired Chinese sailors. They were ideal labour: hard workers for low wages. After the strike, middlemen brought more Chinese sailors and dockers to the Netherlands.

They were housed in shabby boarding houses, in Katendrecht in Rotterdam and around Binnen Bantammerstraat in Amsterdam. Many of the sailors had become addicted to opium to escape their harsh existence. The middlemen profited from the labour, rent and opium use of Chinese migrants.

In the Netherlands, opium had been banned as a recreational drug since 1919, but the Dutch government tolerated its use in the Chinese community. For a long time, rival Chinese gangs were left free to carry out opium and arms smuggling, extortion and killings. Until they introduced heroin in around 1970 and it became a wider Dutch problem.

OBJECTS TIME PERIOD 1

Painting: Chinese man smoking opium

The original 1938 painting is by Dolf Henkes, a Rotterdam painter (1903–1989). His work depicts the world around him, in this case the Chinese community in Katendrecht. The cellars of boarding houses were home to opium dens, rooms where users could smoke opium.

Cultural Heritage Agency – bequest from Dolf Henkes, AB-13363, reproduction

1. Opium pipes

Most opium pipes are wooden, like the pipe with the brown porcelain bowl. Opium is heated in the bowl until it vaporises and then inhaled, a kind of early form of vaping. The brass opium pipe is a Chinese travel pipe. The holder serves as a stand for the pipe and can be used to store and heat the opium. The pipe inserts into the opening at the rear of the holder. 1945–1955; 1900–1950

2. Opium pipe from Katendrecht

The opium pipe with red glazed earthenware pipe bowl was confiscated by the Rotterdam police on Katendrecht in 1930. This elongated model is probably made of pearwood. The pipe bowl is spherical and has a small hole at the top. The so-called brass ‘saddle’, on which the pipe bowl is mounted, is decorated with swaying opium plants and Chinese characters. 1880–1900 Streekmuseum Jan Anderson Collection, 24447

3. Opium storage container

The glass butter dish inscribed with ‘Van der Berghs Blue Band Margarine’ contained Chinese opium, now dried out, hard and unusable. Apparently, for the humble user, this dish was a handy storage container for their opium. More affluent users had opium boxes made of luxury materials, sometimes also richly decorated. 1945–1955

4. Opium lamp and smoking kit

To heat opium, you need a burner. This simple opium lamp consists of a base with an oil chamber, the burner with cotton wick, and on top of it the conical glass chimney. The pipe bowl was held over the flame. Some users had a complete smoking kit, where opium, the burner and other things like needles and pipe scrapers were kept (brass smoking kit). 1945–1955; 1900–1950

5. Ship inspection report

The Import Duty & Excise Duties chief inspector reports the seizure of a total of 280 grams of refined opium, an opium lamp and pipe bowl. The goods were handed over to the Rotterdam municipal police, along with one of the ten Chinese crew members. He had tossed a package of opium overboard, which was fished out of the water. The suspect was sentenced to one month in prison. 1949

6. Opium box

This box, with gold-coloured Chinese characters and a flowering branch on its lid, contained opium. It was found during a ship inspection, hidden under the alternator in the engine room. The box was discovered when the cover plate of the alternator was unscrewed. 1945–1955

7. Penalty for breaching the Opium Act

This passport, issued by the Chinese Consulate in Amsterdam in 1923, belonged to a 28-year-old Chinese crew member. On 29 May 1929, Rotterdam’s chief commissioner of police had this man deported from the Netherlands for violating the Opium Act. The sailor probably belonged to the group of Chinese who increasingly settled in Katendrecht (Rotterdam) from 1911 onwards.

Maritiem Museum Rotterdam Collection, H 1903

Photo credits:

Photo Perron Nul: Ton den Haan, Perron Nul, Rotterdam. 1994

National Museum of Photography, THA-94300-35

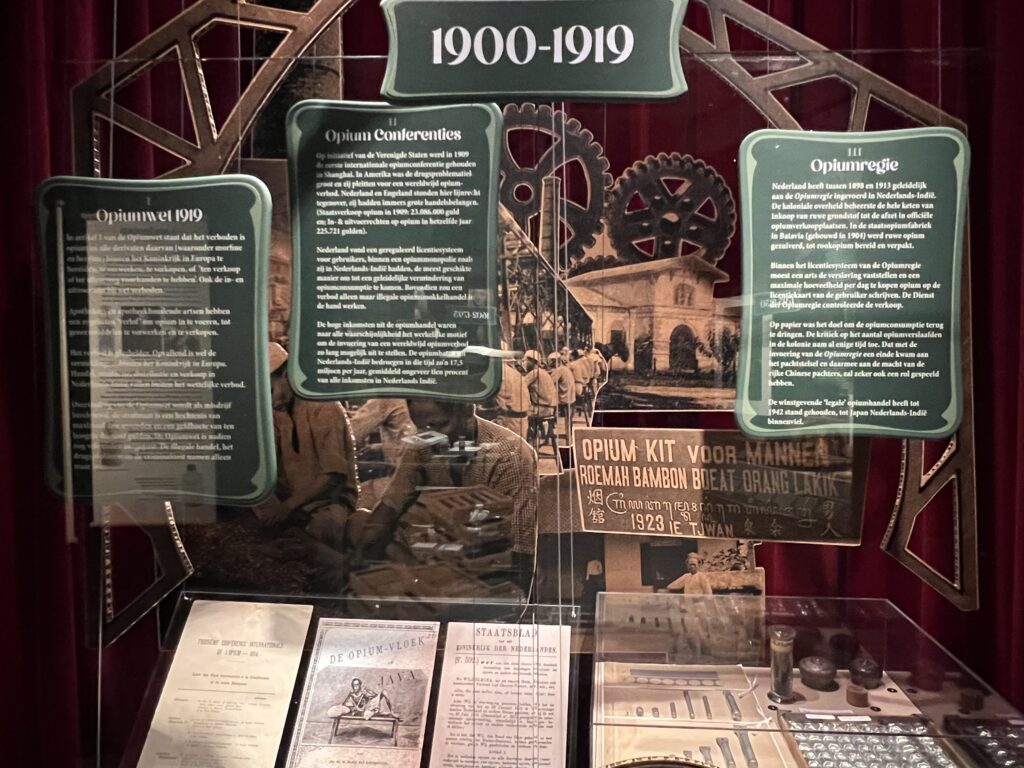

TIME PERIOD 2: 1900-1919

I 1919 OPIUM ACT

II Section 1 of the Opium Act states that, within the Kingdom in Europe, it is forbidden to prepare, process or sell opium and all its derivatives (including morphine and heroin), or hold any of the above in stock for sale or delivery. Import and export was also prohibited by this law.

Pharmacists and dispensing physicians, however, had so-called ‘leave’ (a permit) to import opium and process it into medicine for sale.

The ban was crystal clear. What is striking, however, is the statement: ‘[…] within the Kingdom in Europe’.The legal prohibition of trade in opium and its production, distribution and sale did not apply to the Dutch East Indies.

Violation of the Opium Act was considered a misdemeanour. The penalty was imprisonment for up to three months and a fine of up to 1,000 guilders. The Opium Act has since been amended many times. But drug trafficking, the drug problem and drug-related crime have only increased.

II OPIUM CONDERENCES

At the initiative of the United States, the international opium commission met for the first time in Shanghai in 1909. The Americans wanted a worldwide opium ban because the drug problem in the US was serious. The Dutch and British were diametrically opposed to this, as they had major interests in the opium trade. (Dutch state sales of opium in 1909: 23,086,000 guilders; import and export duties on opium in the same year: 225,721 guilders.)

The Netherlands believed the most appropriate way to achieve a gradual reduction in opium use was to have a regulated licensing system for users, within an opium monopoly, like the one they had in the Dutch East Indies. Moreover, prohibition would only encourage illegal opium smuggling.

In all likelihood, the high revenue from the opium trade was the real motive for delaying the introduction of a global opium ban for as long as possible. At the time, revenue from opium from the Dutch East Indies amounted to some 17.5 million guilders annually, on average about ten per cent of all revenues from the colony.

III OPIUMREGIE (OPIUM MONOPOLY)

From 1898 to 1913, the Netherlands gradually introduced an opium monopoly in the Dutch East Indies. The colonial administration controlled the entire opium chain, from the procurement of raw opium to selling it at licensed opium dens. At the state opium factory in Batavia (built in 1904), raw opium was purified, processed into smokable opium and packaged.

Under the opium monopoly licence system, a doctor had to diagnose addiction and state on the user’s licence the maximum amount of opium they could buy daily. The opium monopoly agency monitored sales.

On paper, the aim was to reduce opium use. Criticism of the number of opium addicts in the colony had been increasing for some time. The fact that the introduction of the opium monopoly brought an end to the opium tax farming system and thus eroded the power of rich Chinese tax farmers would also have played a role.

The profitable ‘legal’ opium trade lasted until 1942, when Japan invaded the Dutch East Indies.

OBJECTS TIME PERIOD 2

Opium Conference & Opium Act

The second opium conference was held in The Hague in late 1911. The page on display shows the participating countries and

the locations where the delegates were hosted. In January 1912, the first International Opium Convention was signed, to take effect in 1915. In the Netherlands, it still took a long time for a separate Opium Act to enter into force. The law was published in the Official Gazette on 4 October 1919. Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal Collection

Magazine: The Curse of Opium in Java

In 1890, the year it was founded, the Anti-Opium League (Anti-Opium-Bond) published an edition of its magazine entitled: The Curse of Opium in Java. The League’s aim was to combat opium use in the Dutch East Indies and wake up people in the Netherlands with their criticism of the opium policy.

1. Opium tube sample card

Raw opium was processed into smokable opium at the state factory. Workers packed this refined opium into tin tubes. Each tube was marked with the stamped text: ‘Opium-regie N.L.’ followed by the date of manufacture. There were seven different-sized tubes, holding different quantities of opium. The most common size of tube could hold 1 mata of opium: 386 milligrams. 1910–1940

Utrecht University Museum Collection

2. Opium trade packaging

The tin tubes of state opium were packed in crates for distribution to official sales locations. The crates were nailed shut and sealed. The seals were inscribed with: ‘Opium-regie Ned Indie’ and the coat of arms of the Netherlands. The trade packaging contained 250 tubes, divided into compartments of five. 1910–1940

Utrecht University Museum Collection

3. Djitjing – state opium marker

The prepared smokable opium from the state opium factory was called tjandoe. Djitjing was added to this official opium as a chemical marker to distinguish between legal and illegal opium because it left behind a residue in opium pipes. This made it easy to determine during checks whether the opium smoked had been tjandoe or tjandoe glap, as illegal opium was known. 1910–1940

Utrecht University Museum Collection

4. Opium boxes

More affluent users stored their opium in beautiful boxes. These two silver boxes both date from around 1900 and are believed to come from the Dutch East Indies, today’s Indonesia. Each box is richly decorated.

5. Box of prepared opium

This beechwood box with ‘Bereide Opium China’ written in black ink on its lid, belongs to the Maatschappij tot Nut van ‘t Algemeen (Society for Public Welfare). This society distributed colonial products from its collection among its own schools. 1945–1950

Photo credits:

Photographs of the exterior and interior of Weltevreden, the state opium factory. Photographs of workers in the factory filling room, putting opium into tubes and packing the tubes into crates.Photograph of a licensed opium den with signboard.

Stichting Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen Collection, TM 60055035, TM 10012174, TM 10012175, TM 60023660304

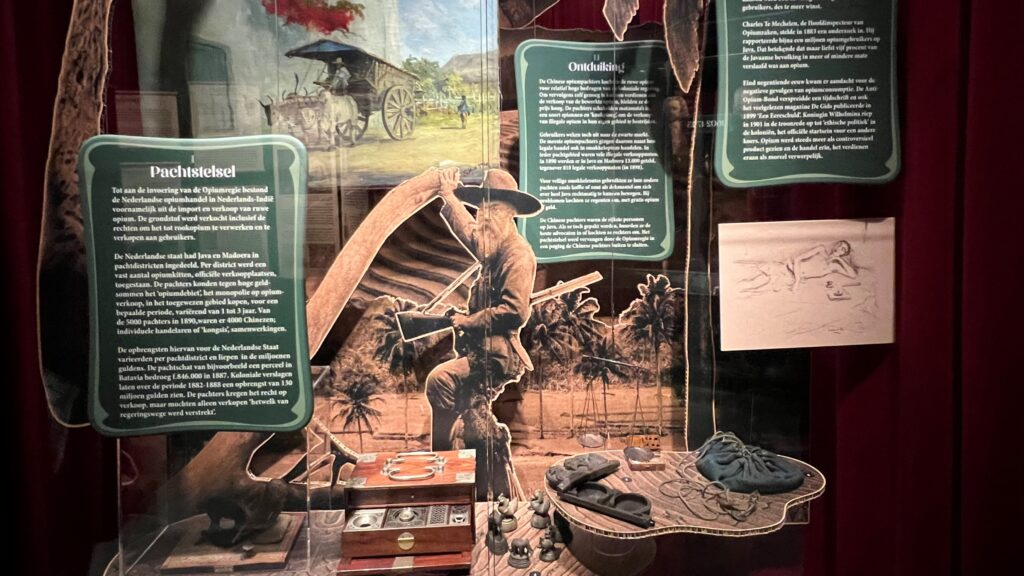

TIME PERIOD 3: 1850-1900

I TAX FARMING SYSTEM

Up until the introduction of the opium monopoly, the Dutch opium trade in the Dutch East Indies mainly consisted of the import and sale of raw opium. The raw material was sold along with the right to process it into smokable opium and sell it to users.

The Dutch state had divided Java and Madura into tax farming districts. A fixed number of licensed opium dens where opium was sold were allowed in each district. In return for a high cash sum, tax farmers could buy an opium concession (a kind of lease), giving them the exclusive right to process and sell opium in a designated area for a fixed period, ranging from 1 to 3 years. In 1890, four thousand of the five thousand tax farmers were Chinese, either individuals or kongsis (syndicates).

The revenue the Dutch state earned from tax farming ran into millions of guilders, although it varied from one concession area to another. For example, in 1887, the state’s revenue from an opium concession in Batavia amounted to 846,000 guilders. Colonial records show revenues of 130 million guilders for the period from 1882 to 1888. Although tax farmers were granted the right to sell opium, they were only allowed to sell opium they procured from the colonial administration.

II CIRCUMVENTION

Chinese opium tax farmers bought the raw opium from the colonial administration at relatively high prices. Then, to earn enough for themselves from selling processed opium, they kept their retail prices high. The tax farmers hired mata matas, ninja-like informers and thugs, to tackle the sale of illegal opium in their own districts.

But users turned to the black market anyway. So, most opium tax farmers started trading in smuggled opium on top of their legal trade. There were many illegal opium dens in each concession area; in 1890, 13,000 were recorded in Java and Madura, compared to 818 licensed dens in 1898.

Tax farmers used their other concessions (like coffee or salt) as cover to move illegal opium all over Java. If they got into trouble, they bribed regents with money or free opium.

Chinese tax farmers were the richest people in Java. If they got caught smuggling, they hired the best lawyers or bribed judges. The tax farming system was replaced by the opium monopoly (Opiumregie) in an attempt to push out the Chinese tax farmers.

III ONE MILLION USERS

The administration of the Dutch East Indies tolerated the sale of illegal opium. The number of both licensed and illegal opium dens increased. As supply increased, so did demand. The more users, the more profit.

Charles Te Mechelen, later the Chief Inspector of Opium Affairs, conducted an investigation in 1883. He reported nearly one million opium users in Java. This meant that a staggering five percent of the Javanese population was addicted to opium to some degree.

In the late nineteenth century, attention began to turn to the negative effects of opium use. The Anti-Opium League (Anti-Opium-Bond) circulated a periodical and the widely read magazine De Gids also published the article ‘A Debt of Honour’ in 1899. Queen Wilhelmina called for ‘ethical politics’ in the colonies in the 1901 Queen’s Speech, officially launching a different approach. Opium was increasingly seen as a controversial product and trading in it and profiting from it, as morally reprehensible.

OBJECTS TIME PERIOD 3

Painting: Cart with Water Buffaloes

S.W.N. Tho’s painting, done in Indonesia, shows two water buffaloes pulling a cart. Across the island of Java, these carts were used to transport goods. Traders tried to acquire other concessions besides opium, including coffee, salt and animal slaughter. Legal concessions provided an excellent cover for transporting illegal goods everywhere. 1945–1960

1. Javanese Man Smoking Opium

Users of opium in Java were mostly from lower social groups, such as coolies, unskilled/indentured labourers, day labourers, coffee pickers, cart drivers, water carriers, etc. Other opium users included farmers with their own land, such as owners of a tegal (dry field) or sawah (rice field), grass and wood sellers, owners of a warong (shop, food stall, kiosk) and tobacco traders. Circa 1890

Utrecht University Museum Collection

2. Opium travel box

The hardwood opium travel box contains essentials for an opium user: an oil lamp, a lamp-chimney holder and several opium jars (China). 1880–1910

Amsterdam Pipe Museum Collection, 16.006 and 18.011

3. Opium weights

The two bronze opium weights in the shape of the Garuda (about 320 grams) date from the 19th century. These animal weights became known in the West as opium weights, but in fact they had been used for centuries to weigh all kinds of goods in Thailand, Burma (now Myanmar) and China, among others. The Garuda appears as a national symbol on Indonesia’s coat of arms.

4. Opium weights

Many weights were made in the shape of animals, such as the two hinthas, birds surrounded by myth that most closely resemble ducks. The hinthas and elephants are both part of a larger series. Such weights often come in multiples of a kyat (roughly 16 grams).

Stichting Farmaceutisch Erfgoed, Grendel Collection

5. Opium scales cases

The beautifully shaped wooden travel scales case from the Dutch East Indies has engraved decorations: the Garuda in the water is carrying a temple on its back. The Garuda is a mythological bird of great symbolism. The wooden pocket case was seized by Customs along with a consignment of narcotics. The case holds a set of scales, cylindrical weights and plates from 1/8 to 10 grams. Circa 1900; 1800–1899

6. Opium pouch

This drawstring opium pouch from Thailand is made of blue cotton with a white cotton lining. There are iron rings along the edges through which the drawstring passes and can be tightened. The drawstring has a rectangular horn lock and a Chinese lucky coin at its end. 1900–1940

Amsterdam Pipe Museum Collection, 13.712

Lithograph Opium Smoker

This lithograph by Marius Bauer (1877–1932) shows a reclining figure with a pipe and an oil lamp beside him. A ball of opium is heating in the flame of the oil lamp before it can be placed in the pipe. The original print is on handmade Japanese paper.

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Collection, RP-P-1942-29, reproduction

Photo credits:

‘Opium Pope’ Te Mechelen:

The person in the foreground is Charles Te Mechelen (1841–1917), Chief Inspector of Opium Affairs.

Stichting Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen Collection, TM 60050304

Governor-General Daendels

The person at the back is H.W. Daendels (1762–1818), the founder of the tax farming system. In 1809, he introduced the opium tax farming system.

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Collection, SK-A-3790

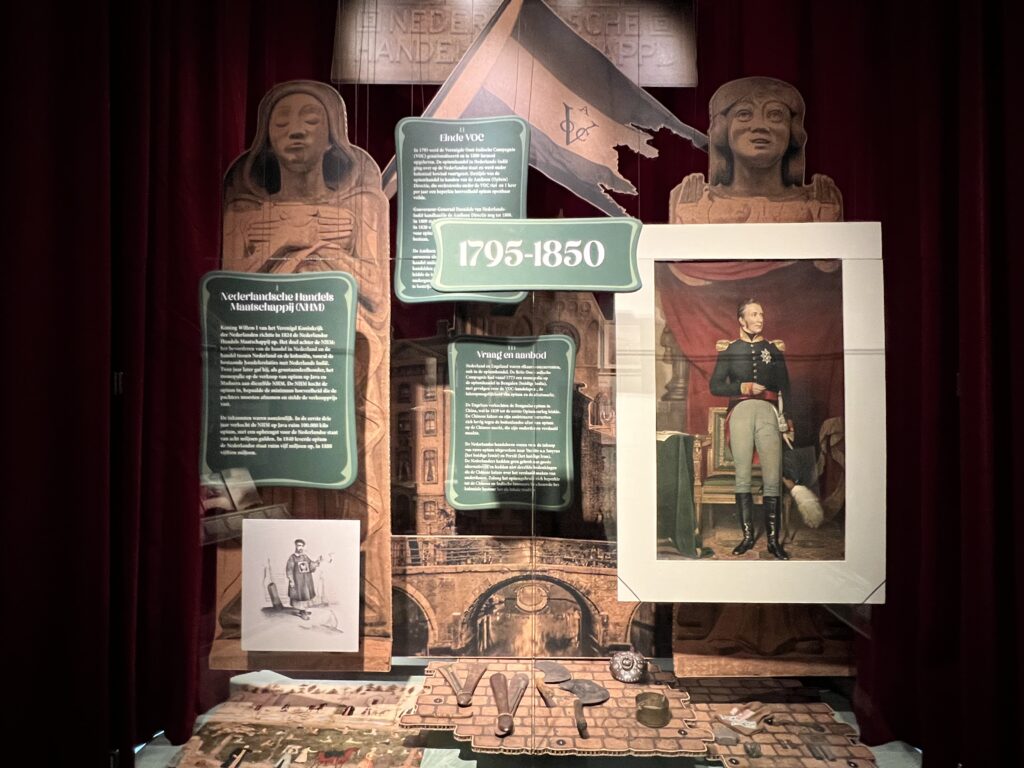

TIME PERIOD 4: 1795-1850

I NEDERLANDSCHE HANDELS MAATSCHAPPIJ (NHM)

King William I of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands founded the NHM (Dutch Trading Company) in 1824. The purpose behind the NHM: to boost trade within the Netherlands and trade between the Netherlands and the colonies – especially the existing trade with the Dutch East Indies. Two years later, as majority shareholder, he gave the monopoly on the sale of opium on Java and Madura to that very same NHM. The NHM procured the opium, determined the minimum quantity that tax farmers had to buy and set the sale price.

Revenues were substantial. In the first three years, the NHM sold over 100,000 kilos of opium in Java, generating revenues for the Dutch state of eight million guilders. In 1840, opium earned the Dutch state over five million guilders, and 15 million in 1888.

II DEMISE OF THE VOC

In 1795, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was nationalised and in 1800 it was officially dissolved. The opium trade in the Dutch East Indies passed to the Dutch state and continued under the colonial administration. At that time, the opium trade was handled by the Amfioen Directie (Opium Directorate). It was supervised by the VOC and could publicly auction a limited quantity of opium once a year.

H.W. Daendels, governor-general of the Dutch East Indies, kept the Opium Directorate in place until 1808. In 1809, he set up the opium tax farming system. There were 372 licensed opium dens in Java by 1820. This tax farming system remained in place for the entire 19th century.

The Opium Directorate was established in 1794 as a new system to combat the illegal opium trade among VOC employees. Many traded privately and smuggled opium. Eventually, corrupt practices at every level of the company led to the downfall of the VOC. All attempts to combat smuggling failed.

III SUPPLY AND DEMAND

The Netherlands and Britain were competitors, including in the opium trade. From 1773, the British East India Company had a monopoly on the opium trade in Bengal (in present-day India), with consequences for the VOC trading post in Bengal, opportunities to purchase opium and the sales market.

The British sold Bengali opium in China, leading to the first Opium War in 1839. The Chinese emperor and his officials fiercely opposed the sale of foreign opium in China because his people were becoming addicts.

To procure raw opium, Dutch traders had diverted to Turkey, including Smyrna (today’s Izmir) and Persia (modern-day Iran). The Dutch were not short of good alternatives and did not have the same reservations as the Chinese emperor about people becoming addicted. As long as opium use was limited to Chinese and Indonesian locals, the colonial administration considered it a domestic tradition.

OBJECTS PERIOD 4

Opium Smoker

The sketch showing a scene with an opium smoker is one of 19 depictions of various Chinese people and animals. Victor Adam is listed as the printmaker on the original 1832 lithograph titled: Sketches of Various Subjects (series title).

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Collection, RP-P-OB-41.291, reproduction

Poppy field in Persia

The scene focuses on a poppy field. Most likely, people are inspecting the poppies for the opium harvest. A unique print, due to its elaborate depiction of a subject that was still regarded as something of a taboo. The work was commissioned by a Dutchman. 1800–1900

Wereldmuseum Rotterdam Collection, WM-68280, photography by Frédérick DeHaan, reproduction

1. Opium harvesting knives

Harvesting opium requires different tools, including a knife for scoring the poppy seed bulb to let the milky sap drip out. The flat wooden case with a hanging hole and string for fastening it, contains two iron harvesting knives. The narrower golf-club-shaped harvesting knife has four blades. 1910–1950; 1930–1960

Amsterdam Pipe Museum Collection, 13.727a/b and 13.728a

2. Opium scrapers

Opium scrapers were used to scrape off the congealed opium gum, a viscous substance, from the poppy seed bulb. The scrapers were specifically designed to suit the shape of the bulb. They have crescent-shaped iron blades. Both have wooden handles. The dark-brown handle is hand carved from a tree branch (Thailand). 1950–1980

Amsterdam Pipe Museum Collection, 13.725 a and c

3. Opium harvesting receptacle

Opium was harvested from the poppy by scraping the congealed gum off the seed bulb and collecting it in a container like this one. This brass harvesting receptacle from Thailand is cylindrical and has a flat base made of red copper. It still has the original string used to hang it around the neck during harvesting. 1900–1940

Amsterdam Pipe Museum Collection, 13.729b

4. Opium pot

This flat round mahogany pot for storing opium is decorated with silver fittings. The pot comes from the Middle East, perhaps Persia, an area where the VOC and its successors purchased some of their opium for trade. The lid has brass fittings and a brass ring. The pot is empty. 1900–1950

5. Chinese and Thai saddle money

The name ‘saddle money’ is derived from the shape of saddles used in the Far East. This silver currency was used across Asia. In remote mountainous areas of northern Thailand, opium crops were still partially paid for in saddle money until World War II. The flat saddle ingot is from China, Yunnan province. The other comes from Lanna, a former independent kingdom in Thailand. 1800–1900; 1296–1558

6. Anman silver

The flat silver bars have Chinese characters at the top and bottom. The other silver bars have Chinese characters on all sides. Chinese Anman silver was used as currency in Cambodia, Burma and Laos. Circa 1895

Colour lithograph Portrait of King William I

This colour lithograph after a painting by C.H. Hodges (1764–1837) shows William I in general’s dress uniform. He owned 4,000 shares – worth 4 million guilders – in the Nederlandsche Handels Maatschappij . As a major shareholder, William I had thus contributed a third of the desired initial capital of 12 million.

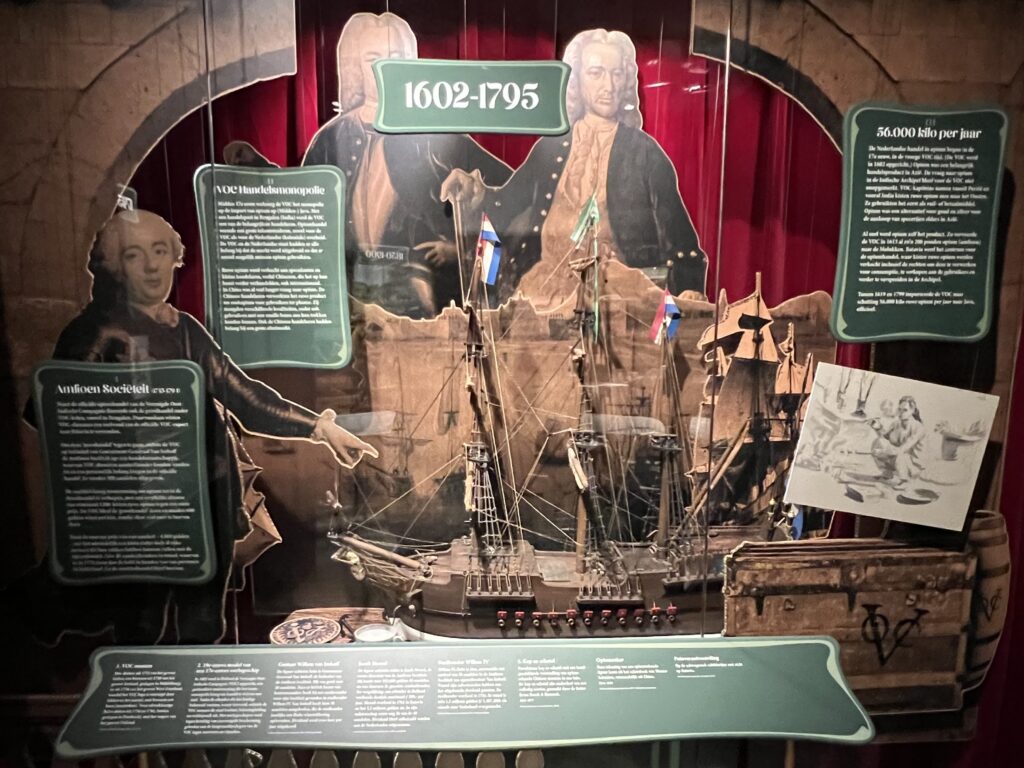

TIME PERIOD 5: 1602-1795

I OPIUM SOCIETY (1745–1794)

Alongside the Dutch East India Company’s official opium trade, private trade flourished among VOC employees, especially in Bengal. From Bengal, VOC officials managed to ship many times more than the official amount of VOC opium to Batavia.

To counter this private trading, at the initiative of Governor-General Van Imhoff, the VOC founded the Opium Society (Amfioen Sociëteit): a trading company in which VOC officials could become shareholders and thus gain a personal stake in the official opium trade. Three hundred shares were issued.

The Society was authorised to sell opium direct to retailers, with a mandatory purchase of at least 1,200 chests of raw opium at a fixed price. The VOC continued to ‘wholesale’ opium and made a profit of 600 guilders per chest, without having to do much for it.

Thanks to the colossal price of a single share – 4,800 guilders – it was ultimately just a small club of already wealthy people who were able to line their pockets through the opium trade. In 1770, over half the shares were owned by some 40 shareholders living in the Netherlands. And the trade in smuggled opium continued.

II VOC TRADE MONOPOLY

In the mid-17th century, the VOC was granted a monopoly for importing opium into Central Java. Through its trading post in Bengal (India), the VOC became one of the world’s leading traders. The opium trade was a major source of income for both the VOC and the colonial administration. The VOC and the Dutch state both had a vested interest in expanding the opium market and ensuring that as many people as possible used the drug.

Raw opium was sold to speculators and small traders, mostly Chinese, who in turn traded it further, including internationally. Opium had already been in demand in China for a long time. Chinese traders refined the raw product into smokable opium for local users. They had a mix of different qualities so that even users with a small purse could get their money’s worth. A large market was also in the interests of these Chinese traders.

III 56,000 KILOS A YEAR

The Dutch trade in opium began in the 17th century, in the early VOC era. (The VOC was founded in 1602.) Opium was an important trade good in Asia. The demand for opium in the Indonesian archipelago did not go unnoticed by the VOC. VOC captains took chests of raw opium to the East from Persia and especially India. At first, they used opium as a means of barter or payment. Opium was an alternative to gold and silver for buying spices elsewhere in Asia.

Soon opium itself became a sales product. In 1613, for instance, the VOC transported some 200 pounds of opium to the Moluccas. Batavia became the centre of the opium trade, where chests of raw opium were sold including the rights to refine it for consumption, sell it to users and distribute it further across the archipelago.

From 1619 to 1799, the VOC officially imported an estimated 56,000 kilos of raw opium per year into Java.

OBJECTS TIME PERIOD 5

1. VOC coins

Three duits: one from the province of Gelderland, struck in 1732; a bronze one from the province of Zeeland, struck in Middelburg in 1748; and one with the VOC logo surrounded by branches and the year, with the rooster (mint mark) at the top, struck in the province of West Friesland in 1756. Two silver half duits from 1756 and 1761, both struck in Dordrecht, with the coat of arms of the province of Holland.

Museum Rotterdam Collection, 8828-C-E-F-G-H

2.19th-century model of a 17th-century warship

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) was founded in Holland in 1602. This private company was granted a state monopoly to trade with Asia. After conquering the islands that form present-day Indonesia, the VOC exercised administration, taxation and justice on behalf of the Dutch state. Warships were used to provide VOC merchant ships with protection from pirates and enemies against payment of convoy fees.

Gustaaf Willem Baron van Imhoff

The person at the back left is Governor-General Van Imhoff, the founder of the Opium Society (Amfioen Sociëteit). He held 20 shares. When outside criticism began to arise, he found an ally for his Society in stadholder William IV. Van Imhoff offered him 30 shares, which provided the stadholder with a hefty annual dividend. Dividends were paid out twice a year. (Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Collection, SK-A-4549)

Jacob Mossel

The person at the back right is Jacob Mossel, the first director of the Opium Society. He was the largest shareholder having bought 40 shares for 192,000 guilders. In comparison, a labourer in Holland at that time earned a maximum of 300 guilders a year. Mossel died in Batavia in 1761, leaving an estate worth 3.2 million guilders, including 26 of his 40 shares. Dividends continued to be paid to his Dutch heirs. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Collection, SK-A-4550

Stadholder William IV

William IV, depicted on the left, accepted chief executive Van Imhoff’s offer of 30 shares in the Opium Society. His heirs, in particular, benefited from the dividend paid out. The stadholder died in 1751. A total of almost 1.2 million guilders (1,187,280) was transferred to the Netherlands via bills of exchange. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Collection, SK-A-6-00

3. Cup and saucer

Porcelain cup and saucer with a hand-painted scene of Chinese men smoking opium in a garden. The cup and saucer are part of a complete tableware set made by the British firm Beech & Hancock. 1862–1877

Streekmuseum Jan Anderson Collection, 24339

Drawing: Opiumroker

This drawing of an opium smoker is from Wouter Schouten’s sketchbook, probably from China. Circa 1660

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Collection, RP-T-1964-364-10, reproduction

Photo credits:

In the background: paintings of views of Batavia. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Collection, SK-A-19 and SK-A-2513

OPIATES & OPIOIDS

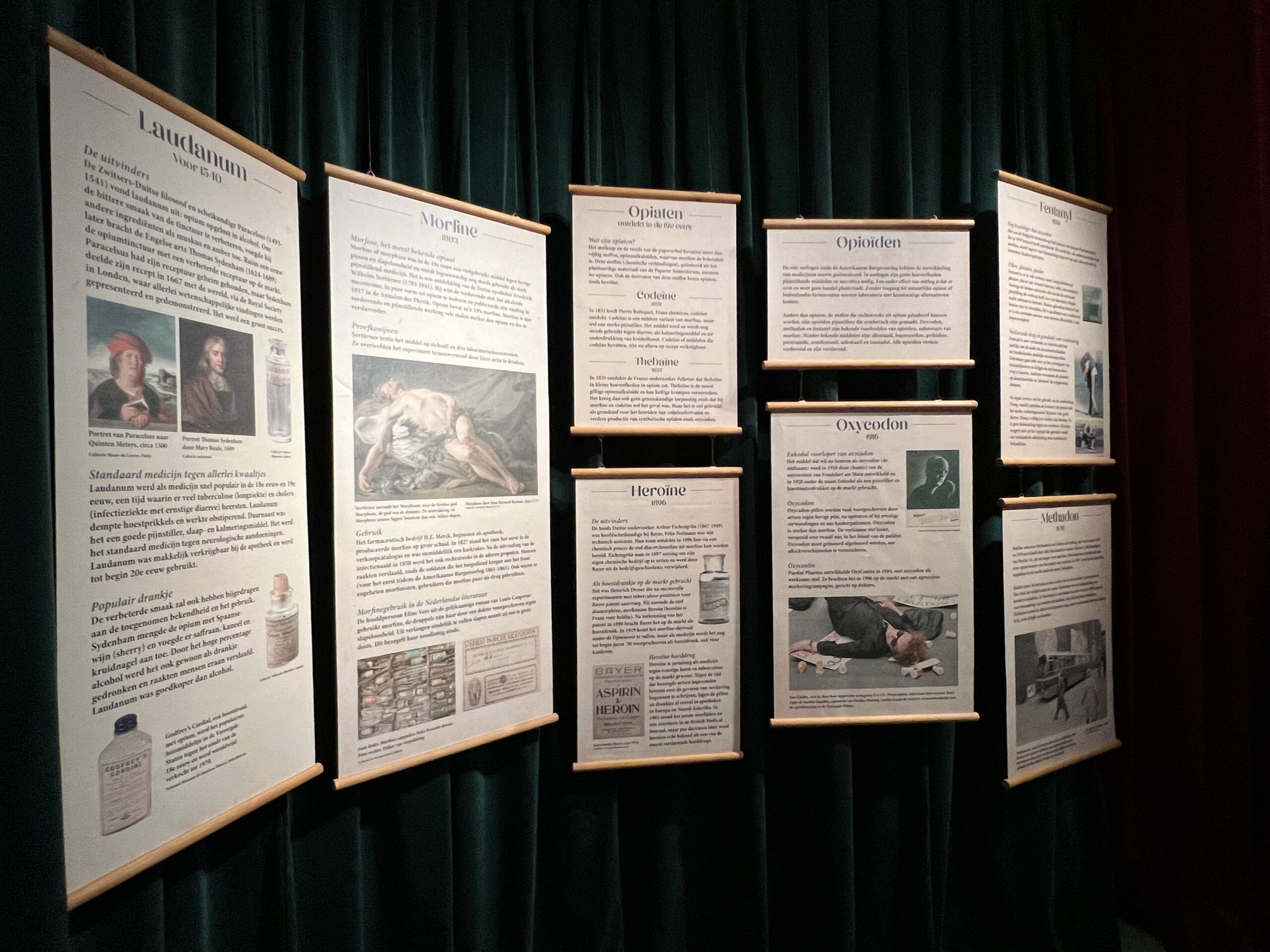

LAUDANUM, before 1540

The inventors

The Swiss-German philosopher and chemist Paracelsus (1493–1541) invented laudanum: opium dissolved in alcohol. To improve the tincture’s bitter taste, he added other ingredients such as musk and amber. More than a century later, the English physician Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689) marketed an opium tincture with an improved recipe. Paracelsus had kept his recipe secret, but Sydenham shared his own improved recipe with the world in 1667, through the Royal Society in London, where all kinds of scientific discoveries were presented and demonstrated. It became a huge success.

Standard medicine for all kinds of ailments

Laudanum quickly became popular as a medicine in the 18th and 19th centuries, a time when tuberculosis (lung disease) and cholera (infectious disease with severe diarrhoea) were common. Laudanum suppressed coughing and had a constipating effect. It was also a good painkiller, sleep aid and sedative. It became the standard medicine to treat neurological disorders. Laudanum was easily available from pharmacies and was used until the early 20th century.

Popular drink

The improved flavour of laudanum would also have contributed to its increased popularity and use. Sydenham mixed the opium with Spanish wine (sherry) and added saffron, cinnamon and cloves. Due to its high percentage of alcohol, laudanum was also consumed simply as a drink and people became addicted to it. Laudanum was cheaper than alcohol. By the end of the 18th century, Godfrey’s Cordial, a cough medicine containing opium, had become the most popular home remedy in the United States and it was sold worldwide until 1970.

MORPHINE 1803

Morphine, the best-known opiate

In the 19th century, morphine was a common drug for severe pain and insomnia and it is still used today as a strong painkiller. It was discovered by German pharmacist Friedrich Wilhelm Sertürner (1783–1841). He managed to isolate a pure form of the narcotic substance in opium: morphine – and he published his findings in 1817 in the Annalen der Physik. Opium contains about 10% morphine. Morphine is many times stronger than opium in terms of its narcotic and pain-relieving effects and all the more addictive.

Guinea pigs

Sertürner tested the drug on himself and three laboratory assistants. They narrowly survived the experiment by drinking gallons of vinegar.

Use

The pharmaceutical company H.E. Merck, which started as a pharmacy, produced morphine on a large scale. The drug first appeared in the 1827 sales catalogue and was an instant hit. After the invention of the hypodermic syringe in 1850, morphine could be injected directly into the veins. People became addicted – including soldiers from the American Civil War (1861–1865) onwards, who were administered it at the front. There were also so-called morphinists, users who took morphine purely as a recreational drug.

Morphine use in Dutch literature

Eline Vere, the main character in Louis Couperus’ novel of the same name, uses morphine. A doctor prescribes her the drops for insomnia. Longing to finally sleep, she takes too large a dose. It seals her tragic fate.

OPIATES DISCOVERED IN THE 19th CENTURY

What are opiates?

The milky sap and fibres of the poppy bulb contain more than 50 substances (opium alkaloids), of which morphine is the best known. These chemical compounds, when isolated from the plant material of the Papaver Somniferum, are called opiates. Derivatives of these substances are also known as opiates, including heroin.

Codeine

In 1832, the French chemist Pierre Robiquet discovered codeine. Codeine is a milder variant of morphine, but still a strong painkiller. The drug was – and still is – prescribed to treat diarrhoea and used as a sedative and cough suppressant. Codeine and substances containing it are now available only on prescription.

Thebaine

In 1835, French researcher Pelletier discovered that a small amount of thebaine was present in opium. Thebaine is the most toxic opium alkaloid and can cause violent cramps. Therefore, unlike morphine and codeine, it was not used for medicinal purposes. But it was used as a raw material for preparing codeine derivatives and to further synthesise opiates like oxycodone.

HEROIN, 1896

The inventors

Jewish German researcher Arthur Eichengrün (1867–1949) was chief chemist at Bayer. Felix Hoffmann was his technical assistant. In 1896, their team discovered how to produce the substance diacetylmorphine from morphine via a chemical process. Eichengrün resigned in 1897 to set up his own chemical company and Bayer erased his name from the company’s history.

Marketed as a cough syrup

It was Heinrich Dreser who filed a patent on behalf of Bayer after successful experiments with tuberculosis patients. He named the substance diamorphine, with the brand name Heroin (héroïne is French for heroine). After the patent was granted in 1898, Bayer marketed the drug as cough medicine. Although this morphine derivative was included in the Opium Act of 1919, it could still be prescribed as medicine (including for children) until the early 1930s.

Heroin, a hard drug

Heroin was on the market for many years as a drug for severe coughs and tuberculosis. By the time concerned doctors started writing letters to the editor about the dangers of addiction, the pills and potions were everywhere in pharmacies in Europe and North America. In 1901, the first overdose death was reported in the British Medical Journal, but it was not until decades later that heroin really became known as one of the most addictive hard drugs.

OPIOIDS

The many wars since the American Civil War greatly stimulated drug development. Wars create a need for large quantities of painkillers and narcotics. Another effect of war is that there is no trade between countries. Without access to natural opium or foreign pharmaceutical companies, laboratories had to come up with man-made alternatives.

Unlike opiates, substances that can be isolated directly from opium, opioids are synthetic painkillers. Oxycodone, methadone and fentanyl are well-known examples of opioids, substitutes for morphine. Lesser-known drugs include: alfentanil, buprenorphine, pethidine, piritramide, remifentanil, sufentanil and tramadol. All opioids are narcotic and addictive.

OXYCODONE, 1916

Eukodal, predecessor of oxycodone

The substance we now know as oxycodone was developed as a painkiller and cough suppressant by chemists at the University of Frankfurt am Main in 1916 and marketed in 1920 under the name Eukodal.

Oxycodone

Doctors often prescribe oxycodone pills to cancer patients and for severe pain after operations or serious injuries. Oxycodone is stronger than morphine. The active ingredient enters the patient’s bloodstream, spread over 12 hours. Oxycodone must be tapered off gradually to reduce withdrawal symptoms.

OxyContin

Purdue Pharma developed OxyContin in 1984, with oxycodone as the active ingredient. They launched it in 1996 with aggressive marketing aimed at doctors.

FENTANYL, 1959

Even stronger than oxycodone

Belgian pharmacologist Paul Janssen of Janssen Pharmaceutica developed fentanyl in 1959. The drug, many times more potent than morphine, is used to treat severe pain, for example, in terminal cancer patients.

Pills, patches, powder

Fentanyl comes in many forms: besides lozenges and patches, there are also fentanyl injections, lollipops and nasal sprays. Apart from pain relief, the drug produces an intense euphoric effect, a reason for the booming illegal fentanyl market. Dealers use fentanyl to cut heroin – fentanyl is cheaper to make and there is a steady supply, whereas heroin depends on poppy crops.

Addictive drug and basis for zombie drug

Fentanyl is highly addictive; in America, just like oxycodone, it leads to tens of thousands of fatal overdoses every year. Users even resort to cutting up fentanyl patches and chewing them. Others heat the patches on aluminium foil and inhale the released fumes.

The worst form, however, is the zombie drug Tranq, in which fentanyl (or another opioid) is mixed with the strong veterinary tranquillizer Xylazine. Tranq is 50 times stronger than heroin. There is no treatment for an overdose. Xylazine does not respond to the antidote used to treat impaired breathing caused by opioids.

METHADONE, 1940

The morphine substitute methadone is a German invention. It was developed in 1937–1939 by Max Bockmühl and Gustav Ehrhart, chemists at Hoechst AG. At the time, Germany could not obtain raw opium for making morphine. In 1947, methadone was admitted to the US market under the name Dolophine.

In the mid-’60s, doctors at Rockefeller University in New York discovered that methadone could be used as a treatment for heroin addiction. In the Netherlands, methadone was first used to treat morphine addicts in 1968 and later to treat heroin addicts. Methadone relieves withdrawal symptoms, but does not cause the euphoria, kick, rush or high of heroin.

MEDICINE CABINET

OPIUM (top shelf of the display)

Opium records 1940–1948 and prescription book

Once the Opium Act took effect, pharmacists could only dispense opium-based drugs on prescription. The prescription, signed by a doctor, had to state the reason for prescribing the drug. In turn, pharmacists had to keep dated dispensing records. The two folders contain dispensing records of opium-based drugs. Stichting Farmaceutisch Erfgoed Collection

Jar with opium cake

Raw opium from Turkey was traded and transported in the form of dried cakes. This opium cake came from Smyrna (Izmir, Turkey). Utrecht University Museum Collection

Opium medicine jars and bottles

The bottle with stopper dates from around 1930 and contained opium extract, according to the label. The glass medicine jar with plastic lid contained opium tablets, in use from 1980 to 2000.

Pantopon entered the market in 1909 as a remedy for pain, cough and stomach complaints. The bottles of Pantopon from the Roche company contained ‘Gesamtalkaloide des Opiums’ tablets. The bottle with brown paper around the cap dates from around 1915, the bottle with metal cap from around 1930. In Europe, Pantopon was taken off the market in 1985.

Stichting Farmaceutisch Erfgoed Collection

MORPHINE (the second top shelf)

Tin with ready-to-use morphine injections

The sealed morphine ampoule syringes in the black tin are from the English firm Roche Products and were manufactured in 1940 for use at the front. The included directions are printed on fabric because paper would have become illegible when wet.

Bonnema morphine tablets

The packaging of the Vilan morphine tablets dates from 1947–1964. The box contained a plastic tube of tablets. Bonnema was a legal manufacturer of pharmaceutical opiates in the Netherlands.

Infusion pump

The morphine infusion pump, manufactured around 1910, was used in the Dijkzigtziekenhuis (now Erasmus Medical Centre). Erasmus MC Collection, 00197

Morphine ampoule boxes

Four different boxes in which morphine ampoules were packed. On the most recent packaging, the use is indicated: ampoules with solution for injection. Stichting Farmaceutisch Erfgoed Collection

Pure morphine bottle

The bottle with stopper dates from around 1900 and the label states it contained pure morphine.

Medicine jar

The transparent glass medicine jar has a home-made label stating ‘MORFINE’. Most probably it contained liquid morphine. 1960–2000

LAUDANUM & VARIOUS OPIOIDS (the second lowest shelf)

VARIOUS OPIOIDS

Dilaudid

German pharmaceutical company Knoll launched Dilaudid in tablet and powder form in 1926. Dilaudid is synthetic morphine with a strong narcotic effect. The box dates from 1926–1940 and contained tablets. The bottle contained powder, which had to be dissolved in a liquid for intravenous or oral intake. The bottle dates from 1926–1975.

Dolantin

Dolantin is a brand name for pethidine, a fast-acting narcotic. It was synthesised by Hoechst in the 1930s and later manufactured by Bayer. The 1965 packaging holds a vial that contained Dolantin drops.

Doloneurine

Doloneurine is a strong painkiller, pethidine hydrochloride. The packaging dates from 1970–1980 and contained 100 tablets of 25 mg each.

Burgodin

Two boxes of Burgodin bezitramide, packaging from around 1995. Burgodin is a strong painkiller. Janssen Pharmaceutica discovered the opioid bezitramide in 1961 and marketed it under the brand name Burgodin in 1976. In 2004, the drug was withdrawn from the market after a number of fatal overdoses.

Novocodon and Fentanyl packaging

Novocodon is a brand name for oxycodone (active ingredient) made by Nourypharma Oss Fabr.: Verenigde Pharmaceutische Fabrieken N.V., Apeldoorn. The packaging dates from 1970–1980. Fentanyl patches with the effect of morphine come in various dosages.

LAUDANUM

Apothecary jars

Until the early 20th century, laudanum was prescribed for various ailments under different brand names. In the 18th century, pharmacists stored this opium tincture, in a more solid form, in special jars. The Delft Blue jar with brass lid and the inscription ‘L/Opiat’ is one example. The jar without a lid with the inscription ‘P:Laudan:opiat’ dates from 1723–1763. Rijksmuseum Boerhaave Collection, V03840 and V10182

Laudanum bottles

One of the bottles contained laudanum made to the original recipe of Sydenham, who transformed the drug in the 17th century. The bottle labelled ‘Laudanum Poison’ shows that laudanum was known to be toxic and thus had to be used with caution. Stichting Farmaceutisch Erfgoed Collection

METHADONE (lowest shelf)

Methadone case

The methadone case, a converted Samsonite attaché case, has a plywood shelf with 58 round holes to hold jars of methadone. The case was used by the municipal pharmacy. ‘O.H.V.A.’ is the Dutch abbreviation for the heroin addicts shelter in Afrikaanderwijk (Rotterdam).

In the basement of the municipal pharmacy on Schiedamsedijk, daily doses of methadone were prepared and measured out for each registered patient. The doses were taken to distribution points around the city in such methadone cases and dispensed to addicts.

Museum Rotterdam Collection, 68206-1.A-B

OUTRO

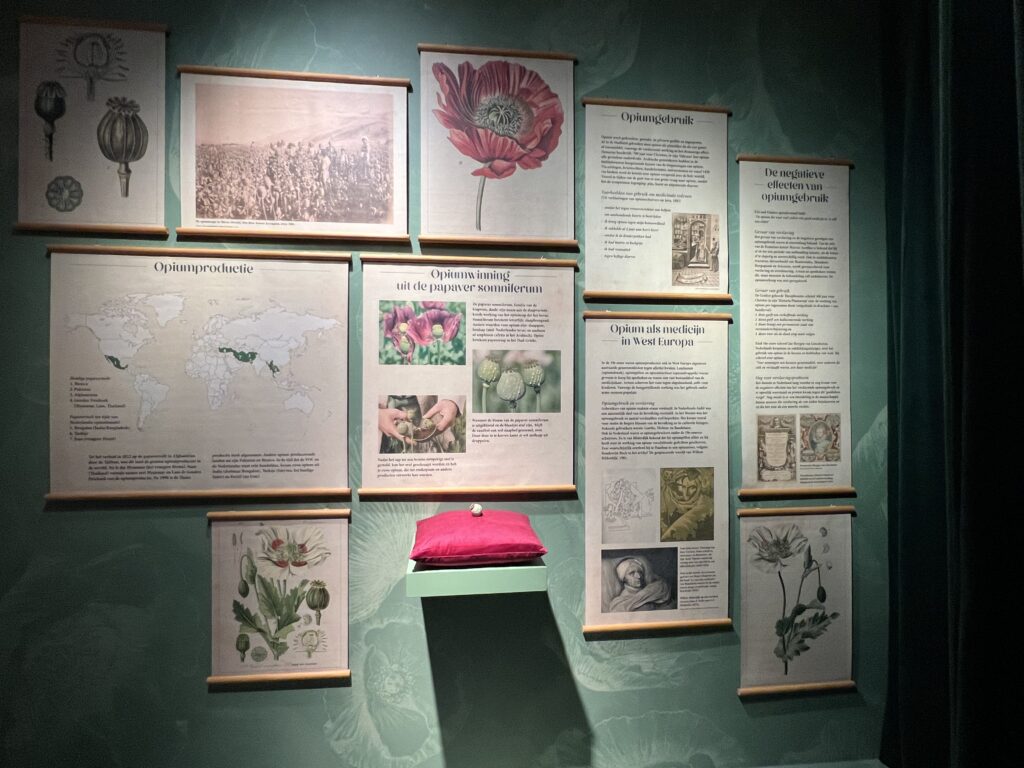

OPIUM PRODUCTION

Until the Taliban banned poppy cultivation in 2022, Afghanistan was the world’s largest opium producer. Now it is Myanmar (formerly Burma). Siam (Thailand) together with Myanmar and Laos used to be known as the Golden Triangle of opium production. Thai production declined sharply after 1990. Other opium-producing countries today include Pakistan and Mexico. At the time when the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch state traded in raw opium, it came from India (Bengal), Turkey (Smyrna, modern-day Izmir) and Persia (now Iran).

EXTRACTING OPIUM FROM THE PAPAVER SOMNIFERUM

Papaver somniferum, the opium poppy, gets its name from the soporific effects of its milky sap. Somniferum literally means ‘sleep-bringing’. Other words for opium are: poppy tears, joy plant and afyūn (in Arabic). Ópion means poppy sap in ancient Greek.

When the flower of the Papaver somniferum has finished flowering and the leaves have fallen, the seed pod, also known as the seed bulb, remains. Scoring it causes white milky sap to drip out.

After the sap congeals into a brown viscous substance, it can be scraped off and you have raw opium, which can be made into smokable opium and other products.

OPIUM USE

Opium was drunk, smoked, swallowed in pill form and injected.

Even in ancient times, opium was used both as a painkiller and a recreational drug and intoxicant due to its hypnotic and euphoric effects. In his Odyssey (700 BCE), Homer describes how opium suppresses all feelings. Arab physicians in the Middle Ages had sophisticated knowledge of opium’s uses.

Knowledge of opium was spread around the world through wars, crusades, trade routes, universities and – from 1450 – also through books.

Especially in times of plague, opium was in high demand as it counteracted the symptoms: pain, cough and debilitating diarrhoea.

Examples of medicinal use (From statements by opium users in Java, 1885)

– because it would help alleviate women’s problems

– to fight persistent fever

– I was given opium for shortness of breath

– I had been struggling with beriberi for 2 years

– because I had chicken pox

– I had fever and stomach aches

– I had rheumatism

– to treat severe diarrhoea

OPIUM USE AS MEDICINE IN WESTERN EUROPE

In 19th-century Western Europe, opium products were also widely accepted as remedies for all kinds of ailments. Laudanum (opium tincture), opium pills and opium drops were readily available in pharmacies and were regular items in medicine cabinets in homes. Doctors prescribed opium for insomnia, even for children. Thanks to its hunger-suppressant effect, its use was popular among the poor.

Opium use and addiction

Users of opium became addicted to it. In the Dutch East Indies, a significant proportion of the population was addicted. In the West, opium use and the number of addicts was much more limited. It was most common among the upper classes of the population and in creative circles. Well-known users included Goethe, Dickens and Baudelaire.

There were also opium users among 19th-century writers in the Netherlands. Bilderdijk, for instance, is known to have taken opium pills and he wrote several poems about the effects of opium. Bilderdijk’s death in Haarlem, according to Boudewijn Büch in his 1981 article De geopiaceerde wereld van Willem Bilderdijk (‘The Opiated World of Willem Bilderdijk’), was very likely due to acute opium intoxication.

THE NEGATIVE EFFECTS OF OPIUM

An old Eastern proverb says: The opium that is a good medicine for many sick people is itself a disease.

Danger of addiction

The danger of addiction and the negative effects of opium use had been known for centuries. Marcus Aurelius’ physician is known to have occasionally introduced periods of abstinence when the Roman emperor became overly sleepy and complacent. Medieval tracts, for instance by Maimonides, Theodoric Borgognoni and Avicenna, also warned about addiction and overdosage. Doctors and pharmacists knew this, but they had to work out the treatment themselves. The sale of opium was not regulated.

Dangers of opium use

In 300 BCE, the Greek scholar Theophrastus wrote in his Historia Plantarum about the effects of opium per dose taken (expressed in drachmae = handfuls):

1 dose has an uplifting effect

2 doses produce delusions

3 doses produce a permanent state of madness and

4 doses result in death

In the late 16th century, Jan Huygen van Linschoten, a Dutch merchant and explorer, wrote about the use of opium in the ports and courts of Asia. He wrote of opium:

To some a luxurious recreational drug, to others who were sick and addicted, an expensive medicine.

Awareness of the addiction problem

In the Netherlands, it took a long time for the negative effects of opium addiction to be recognised and for there to be open resistance to and protest against this ‘godless poison’. Today, society is still divided into people who see addiction as a disease and those who see it as the result of weak character and moral failure.